One Writer’s Discovery of the Pacific Railroad Surveys

by Jodi Daynard

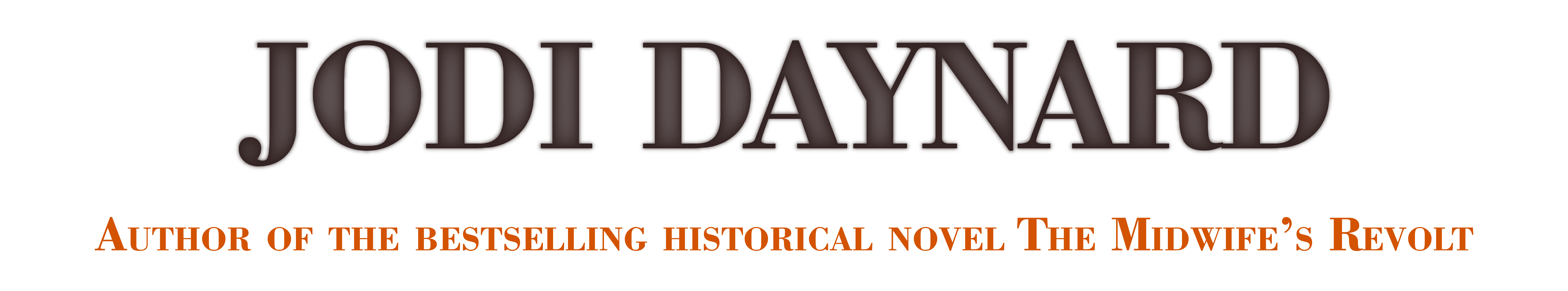

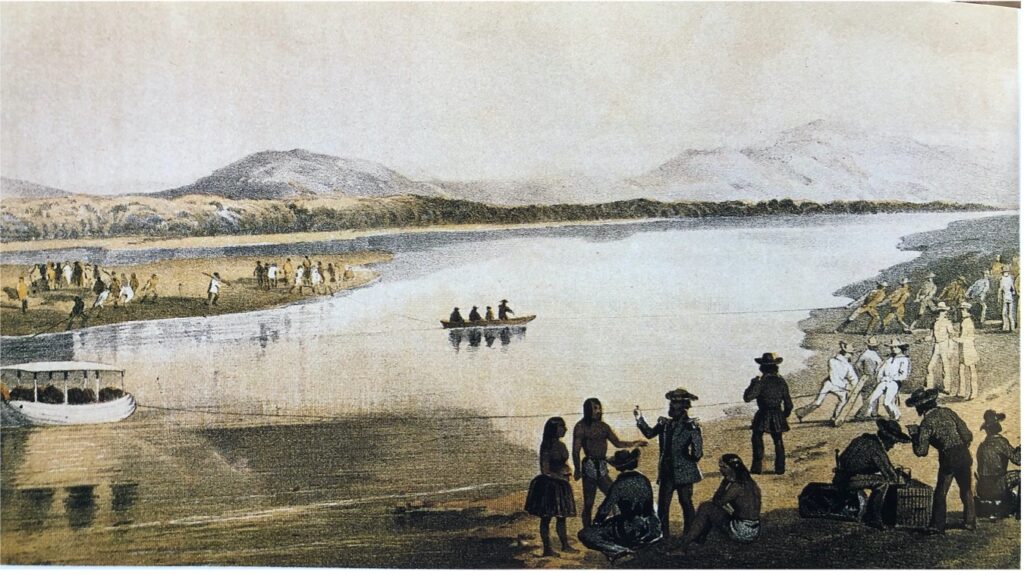

My connection to the Union Pacific is a personal one. In 2013, while clearing out my childhood home after my father’s death, I came across a large, inauspicious old tome with a flaking leather binding. Its title was even less promising: Reports of Explorations and Surveys, to Ascertain the Most Practicable and Economical Route for a Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. Vol. III. And yet, opening this book, I discovered a virgin American wilderness: dozens of colored lithographic plates depicting lakes, rivers, streams, flora and fauna, and tribes of Native Americans I had never seen before. At once, I was filled with both wonder and a sense of loss. That America, I knew, no longer existed.

Volume III of the Pacific Railroad Surveys was printed in 1856 for members of congress, one of twelve volumes published between 1855 and 1860, comprising the reports from four routes along different latitudes from the Mississippi to the pacific coast, plus a fifth running along the California coast. These surveys had been commissioned by Jefferson Davis, then Secretary of War, and took place in 1853 and 1854. The subsequent volumes were produced largely under the direction of Spencer Fullerton Baird, the Smithsonian’s first curator. Comprising well over 6,000 pages of text and more than 600 drawings and colored lithographs, they are a national treasure that few Americans even know about.

Three years after first opening Volume III, my interest in the Pacific Railroad Surveys had not waned but rather had grown into an obsession, and I knew I had the canvas for my next novel, A Transcontinental Affair.

Two observations about these surveys inspired me: that the world these plates depict is largely gone, and that, ironically, the railroads these surveys sought to bring into being were largely responsible.

Volume III, the one I first perused, describes the 1854-1855 Whipple expedition along the 35th parallel. The team’s artist, Heinrich Baldwin Möllhausen, was a Prussian naturalist, writer, and draftsman of extraordinary gifts; this was his second excursion to the Far West.

The Surveys, under the direction of Spencer Fullerton Baird, the Smithsonian’s first curator, were meant to be scientific excursions, yet there is an undeniable aesthetic component to the artist’s renderings, perhaps for the same reasons that they made good science: their pursuit of accuracy and truth. Knowing the danger and loss of life that were endemic to these expeditions makes one appreciate the art’s transcendent purity even more.

In the end, the expeditions failed to answer the question of the most practicable route to the pacific. This was in part because northern Republicans vehemently rejected Davis’s proposed southern route; and in part because the outbreak of the Civil War made them moot. President Lincoln took up their challenge again after the war, eager to fulfill their promise once the specter of slavery had fled. But another kind of specter lurked, one not even Lincoln could foresee: the total destruction of the pristine wilderness, the buffalo and in the end the Native Americans themselves. The story of the transcontinental railroad is both the story of the birth of modern America and a morality tale for the ages.